AWF v. Goldsmith (Pt. 4): The Pros and Cons of the Majority Opinion, and Some Comfort

Fair use is a magic wand, but you have to wave it every time.

Welcome to Day 4! Here is a quick recap of key points from prior entries:

The plaintiff in AWF v. Goldsmith was not Andy Warhol the artist, but The Andy Warhol Foundation.

Lynn Goldsmith - a professional photographer - did not sue the Foundation; AWF sought a declaratory judgment against Goldsmith.

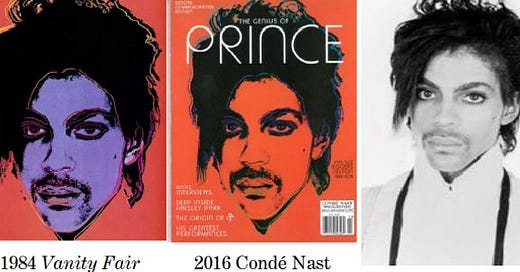

The Supreme Court did not rule on the artwork Orange Prince; it ruled on the use of a reproduction of Orange Prince on a magazine cover [have questions on 1-3, see Day 1].

The Andy Warhol Foundation spent over $2.1 million on legal fees between 2017 and 2021 for a case it brought to the courts, over a $10,000 licensing fee it received from a magazine [the math seems off, see Day 2].

Goldsmith expressly disclaimed all remedies as to museum display, collector possession, and sales of Orange Prince. That was legalese for “Goldsmith did not sue AWF over the actual artwork Orange Prince and in fact seems to have always been fine with the artwork’s existence.” [see Day 3, or keep reading below]

To date, most articles I have seen about the case have been reductive and misleading because they make the same conceptual collapse between Orange Prince (The Artwork) and a reproduction of Orange Prince that graced the cover of Condé Nast’s 2016 special edition “The Genius of Prince” (The Cover).1

However, because you read the last three installments, you now comprehend that The Artwork and The Cover are not the same thing; understand that the Court ruled on The Cover (not The Artwork); and know that the Court did not speak to The Artwork because everyone - even Goldsmith! - agreed that The Artwork is likely transformative.2

So, today we’re moving on and covering the majority opinion.

Like all judicial opinions, AWF v. Goldsmith has pros and cons. It resolves issues and raises others. It didn’t add much new material to our understanding of fair use. If anything, it often reads like Sotomayor is asking: “Did you people even read Campbell v. Acuff-Rose?”3

For reference, Campbell was decided in 1993. The ruling helped define fair use, particularly concerning parody, satire, and music. Campbell changed all creative industries because its ruling was later applied to literature, visual art, music, and many forms of technology. Creativity didn’t fall off a cliff after Campbell, and it won’t fall off a cliff after AWF v. Goldsmith (more to come tomorrow!).

That said, the music industry had to respond to that ruling. Consequently, people figured out ways to license, reuse, and continue to make music. In fact, music has a lot to teach art about its possible futures. Visual artists have 30 years of mistakes and triumphs to learn from, and brilliant scholars to lead us through that history.4

Okay, back to it - as I was saying, the majority opinion is not perfect. However, it did satisfy me as both art historian and lawyer. It made me feel calmer about the future of contemporary art, despite all the pearl-clutching.

Let’s dig in!

THE PROS

1. Fair use is a magic wand, but…

When an Appropriation Artist creates a new artwork using pre-existing material (like Warhol; silkscreen), he holds a very “thin” copyright over the resulting work (specifically, a copyright over only the new additions). The underlying work is still owned by the Prior Artist (like Goldsmith; photograph), so an Appropriation Artist can’t sell/display/reproduce/distribute his new artwork without (a) getting a license from the Prior Artist or (b) relying on fair use.5

Fair use is a four-part, fact-specific legal balancing test, where judges assess the purpose, nature, amount, and market harm. There are many competing theories that explain how and why fair use works (which I plan to cover in later posts), but when I teach this concept to students, I say fair use is a magic wand. Wave it, and you wash Prior Artist’s rights away.6

AWF’s take on fair use, in a nutshell: If Orange Prince is covered under fair use, then all copies of Orange Prince are also protected under fair use, wherever or whenever they are made, reproduced, distributed, and displayed.

Goldsmith’s take on fair use, in a nutshell: Orange Prince the silkscreen [The Artwork] is one kind of copy and one kind of use, but a digital reproduction of Orange Prince for commercial use [The Cover] is a different kind of copy and different kind of use, one which has a different impact on the underlying copyright holder. We’re OK with the former use but not with the latter use.

Here’s what AWF v. Goldsmith determined: You have to wave the magic wand every time.

Want to sell The Artwork? That’s one kind of spell, and it might work.

Want to display The Artwork? That’s a different kind of spell, and it might work.

Want to reproduce The Artwork and license it for a magazine cover, just like Prior Artist does with the underlying material? That’s another kind of spell, and the fair use wand doesn’t work for that spell.

This ruling is positive for most artists because it gives them the ability to (1) acknowledge fair use in a market that they don’t occupy but (2) push back if another use impacts the market where they sell their work. Furthermore, AWF v. Goldsmith encourages Appropriation Artist not to solely rely on a fair use defense but rather to ask for permission (or secure a license) from the Prior Artist.

Here’s why permission is important: it works both ways. If you don’t have to ask permission to play your favorite band’s song at your political event, then Trump doesn’t have to, either.

I realize that the idea of permission makes everyone freak out. You know what? Robert Rauschenberg put on his big boy pants and asked. Tom Wesselmann asked. Even Andy Warhol asked. They often made friends and mentors in the asking. If they can ask, so can you.7

The law is just a floor. We can proactively and generously expand our own habits and customs around permissions and sharing within our own communities. We can develop cultures of asking rather than taking.

2. No More “Raw Materials”

In theory, all legal subjects should be treated equally under the law. We’d be upset if courts let Brad Pitt and Jenna Ortega drive at a different speed limit than everyone else. That would create a celebrity privilege.

In reality, the law constantly affords privileges to the wealthiest. Remember, AWF spent millions of dollars to see this case through. Your average artist will quit before she sees the inside of a courtroom. The overwhelming majority (80-97%, depending on the data source) of civil cases are settled or dismissed without a trial.8

I’ve already explained how recent fair use jurisprudence (and much of the expert analysis of contemporary art that undergirds these cases) divided artists into “geniuses” and “raw materials.”

Going forward, let’s refer to Celebrity Artists and Working Artists. The chief merit of the opinion is its abolition of those castes, so we can dispense with them, too.

Celebrity Artists tend to behave a little differently than Working Artists.

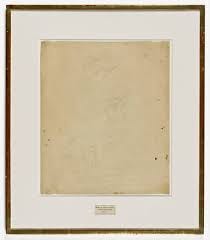

Richard Prince reached out to his friends for permission to use elements incorporated in his monumental collage/painting series Canal Zone, which became the subject of dispute in Cariou v. Prince (2013). He also paid them in trade. He didn’t ask or pay Patrick Cariou, the photographer whose work was foundational to Canal Zone. It wasn’t hard to find Cariou; the photographs were taken from a coffee table published by a Brooklyn publishing house. Prince just didn’t bother.9

Our pearl-clutchers will now ask: “But what if Cariou said no? What if Prince never made Canal Zone? What kind of extraordinary artwork will be missed because of this draconian imposition on creativity?”

By now, I hope you realize that AWF v. Goldsmith imposes no constraint on Prince’s creativity in this example. It imposes a constraint on Prince’s ability to sell his creative works at Gagosian without (a) securing a license and (b) extending some kind of payment to Cariou.

Similarly, Condé Nast likely chose Orange Prince because that image would gain the most attention. AWF v. Goldsmith says “That’s fine, somebody just has to pay Goldsmith, too.”

Yes, this is kind of like resale royalties, and yes, I think we should have a system of resale royalties.10 If you’re an artist who would like to get paid when Big Shot Collector resells your work at a premium, then you understand this concept.11 Payments on each new use is passive income gained while new creative work is being made; it’s a system that benefits Celebrity Artists and Working Artists alike.12

Now, if Goldsmith demands $1,000,000 when AWF only charged a $10,000 fee, then that’s absurd.13 If Cariou says “I want a gazillion dollars!” then Prince rightly says “no thank you.” Yet, we can still move ahead if Prior Artist tells Appropriation Artist “no” or demands an outrageous fee, because our Appropriation Artist can still claim fair use.

AWF v. Goldsmith says that we move on by establishing necessity.14 Necessity is a deeply important part of AWF v. Goldsmith. Essentially, the Court said: “You can claim fair use, but you must substantiate your reasoning for each use every single time.”

This is when the pearl-clutchers clutch again. “But artists can’t explain themselves!”

Artists are perfectly capable of explaining themselves. Warhol was particularly great at explaining himself; he was a compulsive archivist and diarist who chronicled everything, including his struggles to secure permission for pre-existing material and changes he made to facilitate his art practice.15 No one is saying that artists need to know what they’re doing while they’re doing it. But a little reverse-engineering may be in order. There’s a whole discipline that can help artists do this. It’s called art history. Art historians can help artists find the right words. That’s exactly what they’re trained to do.

3. A Bulwark Against Image-Generating AI

Unfettered creative freedom sounds great. In practice, it often means unfettered capitalist predation. Tech CEOs think they’re celebrity geniuses, too.

When AWF’s claim was filed, image-generating AI sounded like science fiction. In 2022, fiction became reality. Companies behind generative AI programs like Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, and DALLE have all claimed fair use when they used copyrighted artworks without consent to train their models. AWF v. Goldsmith makes it much, much more likely that these AI models are not covered under fair use.

Courts can now follow AWF v. Goldsmith to ensure that generative AI programs limit their training and output to:

(a) public domain imagery,

(b) free stock, or

(c) licensed content.

We can’t say that Sotomayor & Co. thought about AI - the justices are not supposed to consider any facts outside those presented by counsel. Yet, justices are humans, too. It might be a happy accident that it worked out this way, but I wonder if the implications of a decision for Warhol were perfectly evident to the seven justices in the majority.

AWF v. Goldsmith can be seen as “judicial activism,” which many activists say they want until it impacts their short-term decisions, net worth, and comfort.16 BrightTunes v. Harrison, another oft-derided opinion, was deeply activist, too. Judge Owen’s introduction of “subconscious copying” makes legal scholars rend their garments, but find me a black woman who hasn’t been treated like The Chiffons in the workplace.17 Judge Owen called a Beatle out for acting like he owned the creativity of a less powerful girl group. In 1976, Owen devised a tidy term to describe the kind of entitlement we’re still struggling to define and redress in 2023. If you’re a professional creative, “subconscious copying” should only scare you if you’re in the habit of claiming you did the group project alone.

AWF v. Goldsmith is an activist opinion, but dear reader, what kind of world do you want to live in? A world where our courts ignore the human toll of the laws they create or a world where the justices give a shit about humans?18

This isn’t about being woke or traditional. This isn’t about being liberal or conservative. This is about being ethical and humane. Four extremely conservative justices were able to side with Sotomayor because it isn’t about further empowering a tiny handful of powerful “geniuses” - it’s about treating all people as something more than “raw materials.”

Which is a really low bar.

THE CONS

For an application besides AI, the future sounds like a total pain in the ass, doesn’t it?

Licensing can be a total pain in the ass, but not for the way you might think.

1. You’ll Need More Licenses

I don’t get emails about Celebrity Artists trying to use a Working Artist’s material. Generally speaking, Celebrity Artists are going to do what they like under the assumption they’re covered by fair use.19

A Working Artist is going to bump up against The Great Licensing Machine: Artists’ Rights Society, ASCAP, and - wait for it - the Foundation itself. A Working Artist is going to encounter even more obstruction from the lawyers, agents, and estates that serve Celebrity Artists.20

If there is a downside to this opinion, it is that agencies and estates will be further empowered to demand that Working Artists, museum curators, and scholars pay exorbitant fees to license images made by Celebrity Artists for reuse purposes. ARS can say no. ARS can take forever. ARS sometimes charges a lot.21

Yet, the answer to the problems posed by The Great Licensing Machine is not changing fair use law in the ways proposed by the Foundation. The only artists who stand to benefit from the relaxed, colloquial version of fair use proposed by the Foundation are clients of ARS.

Turnabout is not fair play in this system. If you try to use an image of a Warhol in your academic article or MFA thesis show, the Foundation will demand a licensing fee, and no editor or curator will let you proceed without the Foundation’s permission.22 (The irony.) I would take the Foundation’s savior-of-culture approach more seriously if they didn’t gatekeep scholars and younger artists this way.

Yes, work will need to be done to ensure that Working Artists can license work efficiently and at reasonable rates. Licensing agencies and artists’ estates (such ARS and the Foundation!) are the ideal candidates to work on these issues. I hope these powerful players will focus their efforts on these issues, rather than burdening Working Artists, scholars, and curators with more fees.

I also hope AWF v. Goldsmith will be a wake-up call to the art and academic publishing industries because a little bravery from these institutions could create widespread change.

2. We Need to Be More Generous Than the Law Requires

Anyone can choose to be more lenient with the obvious fair uses - education, non-commercial, personal - and more skeptical about obvious money-makers.

For the cases in between, Goldsmith’s position is a more sophisticated way to think about copying, reproductions, semiotics, and economics. It’s a little harder to understand than AWF’s position, but copyright is a highly philosophical branch of law with competing and discordant rationales for its existence. It has always been a little harder to understand, and attempts to water copyright down can oftentimes make it more difficult to understand, not less.

Here’s yet another secret: copyright law is just a floor.

Remember, we choose when to enforce our copyrights. Copyright scholar Jessica Litman suggests we ask people what kind of copyright and licensing system they’d like to have, and this is brilliant simplicity.23

We can behave better towards each other than the law requires.

We can create rules that work for our specific communities.

We already have excellent fair use guidelines, and they’re being updated all the time. Here is the guide for artists: Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts.

We can keep updating those guidelines.

We can use Creative Commons licenses.

We can provide licensing templates and affordable legal services.24

Artists can share information with each other about reasonable rates and terms.25

Because nothing is stopping us from being more generous than the law requires, except us.

3. No Bright Line Rule

As stated above, fair use is hard to understand. Like, really, really hard to understand.

On Day 1, I said that Sotomayor’s opinion is a 301 class on the dialectics of meaning. Sotomayor’s opinion is the opposite of “I could paint that.” Her syllabus includes a close reading of the Copyright Act and Campbell, but also Lacan, Adorno, Foucault, Barthes, Benjamin, and Derrida. (Kagan assigned Janson.)

This is great news for scholars; plug Campbell into Google Scholar and you’ll get 7,800 hits. We chewed on that case for 30 years, and AWF v. Goldsmith has given us plenty of material for the next 30 years. That may feel like cold comfort - let’s clutch our pearls again - “because there’s no clarity!”

I think a little diffusion and debate is fine - because I think people are capable of talking things out and collaborating. Lawyers who take an adversarial approach to the law will feel differently. Adversarial approaches are better served by binary rules.

Boiling something subtle and complex down to a bright-line rule that covers every use across visual art, music, literature, film, and code just makes every application difficult and more likely to be characterized as an exception.

Nothing said in the majority opinion prohibits an Appropriation Artist from waving a fair use wand. He can still use the defense; he just has to explain why in every instance.

I know as a society we’ve gotten used to being able to drag and drop, replicate, and remix to our heart’s content. The Court isn’t telling you to stop. The Court is asking you to be more mindful about what you use and how you use it.

Is that so terrible?

If you’re still concerned about the future, I hope this advice from polymath Jaron Lanier helps. Lanier’s wisdom has guided my thinking about appropriation for more than a decade, but it’s as powerful and relevant today as the first time I read it.

Appropriation and reuse are central to all culture, of course, not just digital culture. But to those who want to appropriate another artist’s work, may I suggest some ways to do it that you will probably find rewarding, even though some effort is involved?

a) Internalize what you want to appropriate first, so that it comes out of you as both an appropriation and as your personal expression. A golden example would be Thelonious Monk’s learning stride piano and then turning out his Monkified stride entwinement. I realize it might be intimidating to bring up a stellar example like that … but that’s the path to meaningful culture.

b) Don’t appropriate something just because there’s a dose of novelty in it, even though you have no idea what it meant to the people who made it originally. Connect, understand, or empathize with the people you appropriate from, to the degree you can. It can be hard to understand or connect with other people, even in the best of circumstances: that’s the human condition. Any little bit of awareness across the mysterious interpersonal chasms that separate you from another person is a triumph, and the only source of meaning. (That doesn’t mean that all appropriation has to be based on sympathy. What I’m saying applies equally well to such things as satire and criticism.)

c) Put some effort into finding a way to be financially fair to your sources even if an easy path to do that isn’t laid out for you. Aware appropriation and denatured, sterile appropriation are opposites.”26

That’s very hard and very easy. Don’t try to memorize Lanier’s advice. Put it into practice every day. Take some action like Rauschenberg, Wesselmann, and Warhol himself. Do this for a while, and you’ll eventually live into it.

Lower courts will figure it out. Art historians will step in to help. The Copyright Office will convene panels. A lot of really smart people care deeply about this subject.

It’s not the downfall of Western Civilization.

We will address the dissenting justices’ fears tomorrow.

To remind you, Sotomayor’s opinion doesn’t say that overtly because it cannot; if the Court is asked to rule on The Cover alone, it cannot extend its ruling to The Artwork. A justice can yak about an issue that is not under review, but that’s known as dicta, and it’s not supposed to create controlling law. But lower courts rely on dicta in copyright rulings all the time, often to confusing ends. (Judges yakking about the law is a very funny theme in the oral arguments to this case.)

For my lawyer friends: I am writing for a general audience. I am assuming the level of knowledge about the law shown by my undergraduate students. (Which is to say: none.) I am not linking to Nimmer because there’s no free version of Nimmer. No proper citations, lots of generalizations. We can argue in the journal footnotes. Or meet up for lunch - call me, it’s been too long!

Meet my mentor Jennifer Jenkins. She’s a top authority on the subject. Her research is full of ideas from the history of music and copyright that can be applied to visual art and copyright. Her forthcoming book is called Music Copyright, Creativity, and Culture. It will be out next year.

NB: Using the terms “Appropriation Artist” and “Prior Artist” is a rhetorical tool designed to help you keep thinking of each as a person. Rob and I do this in contracts, too. We never write “the Artist” and “the Client.” Articles create abstractions. Remembering that you’re dealing with a human being is the key to…everything, really.

And now you know why the newsletter is titled “Protect Your Magic.” Magic is an excellent, almost endlessly useful metaphor for intangible legal rules.

Rauschenberg drank part of bottle of whiskey then knocked on DeKooning’s door. I don’t recommend that strategy. Make yourself a nice email template. Have standard language, then add some specific gushing about how much you love the person you’re asking. I review these for clients all the time.

Study Finds Settling Is Better Than Going to Trial. A civil case is brought by a private party against a private party. Divorce, wrongful termination, most intellectual property cases, etc. A criminal case is brought by the state against a citizen. Murder, robbery, arson, etc.

“The repros of women were supplied from friends. Dian Hanson, John McWhinnie, Richard Kern. One repro came from Eric Kroll. I gave each of them a small study in return for their giving. I don’t want to talk about where the Rastas came from.” Richard Prince said that in the press release to his 2014 exhibition as Gagosian. “Richard Prince: Canal Zone,” Gagosian, April 22, 2014.

In parts of Europe, artists get a cut of future sales. Sounds fun, right?

Depending on how everyone treats each other. This is a Pollyanna moment. Keep reading.

AWF says Goldsmith did this, she says she didn’t. It’s not part of the public record. What we know to be true: many brilliant scholars have proposed licensing schemes that prevent the nightmare scenario. The Copyright Office has its pick of great ideas!

We will discuss necessity in rich detail, explaining why Cariou’s work was absolutely necessary to Canal Zone, on Day 5.

Why did Warhol take so many Polaroids? Because he was sued for copyright infringement and decided to start making his own images. Kate Donohue, Andy the Appropriator: The Copyright Battles You Won’t Hear About at The Whitney’s Warhol Exhibit

Britannica, Judicial Activism.

Candace Owens is not an acceptable response to this question.

I, TOO, CANNOT BELIEVE THAT I’M WRITING *THESE* WORDS ABOUT *THIS* COURT.

See above, Richard Prince, who “doesn’t want to talk about” it. See also Mr. Brainwash, Rob Pruitt, Jeff Koons, and that stupid pissing Calvin decal that graces so many trucks in North Carolina.

I do not represent artists who act this way. If a client asked me to charge an exorbitant licensing fee to a less-powerful artist, I would refuse. There are plenty of lawyers happy to take my place.

Not my original thoughts: Art Is Long; Copyrights Can Even Be Longer

This happened to me just last month, in an article about fair use. I staunchly refuse to ask permission for the evidently fair use purpose of commentary and criticism if (1) I’m not being paid for the entry and (2) the artist I’m writing about relied on fair use to make the artwork I’m writing about. My obstinacy can make it very difficult to publish anything about these artists and their artwork in art historical journals.

Jessica Litman, Digital Copyright, 2006, p111.

This one’s my job! More on this soon.

Artists talking to each openly about money would make such a big difference. The hardest question for me to answer is “How much should I ask for in the license agreement?” You tell me, friend! What’s the industry standard? How can we set a fair industry standard? Make sure everyone charges a fair fee. Peer pressure!

Jaron Lanier, You Are Not a Gadget, p276. Dear Mr. Lanier, if you’d for me to take this down, you can reach me at info[at]devosdevine.com. But we both know I just sold a bunch of books. Thank you for inspiring me. Warmly, Katherine