AWF v. Goldsmith (Pt. 1): Misapprehensions, Clarifications, and a Truth Bomb

Your resident copyright lawyer / art historian gets nerdy about the biggest case of her lifetime.

I’ve been waiting for months for the AWF v. Goldsmith opinion to drop. I’ve been waiting years for a case like it. Fortunately, I’m alone in the Vermont woods for a week and have the time and interrupted sleep to get extremely nerdy about the whole business, so away we go:

Preface or “Why you should listen to me about this topic”:

I am an intellectual property lawyer who negotiates copyright licensing agreements every day.

I earned a PhD in Art History. My specific area of expertise is contemporary art, copyright law, and appropriation.

My ultra-specific area is “transformative use.” As in, the ultra-specific legal doctrine under consideration in AWF v. Goldsmith.

Very few people on the planet have thought about the issues in this case as long or as deeply as I have.

Very, very few can think about the issues as a practicing lawyer and as an art historian. You’ll find plenty of brilliant writing by one or the other, but it's extremely rare to find both perspectives in one skull. The dual training allows me to make connections that others don’t. The double perspective also helps me spot errors of characterization or judgment, and explain why those errors are problematic.

We’re going to start our history and analysis of AWF v. Goldsmith by pointing out some errors. This is not to be picky, but to gently trouble the assumptions and beliefs I suspect you hold, and set the foundation and tone for our time together.1

Thanks for getting nerdy with me.

Misapprehension #1: AWF v. Goldsmith eliminates fair use for visual artists!

IT DOES NOT. I’m not going to bury the lede; here’s my take:

AWF v. Goldsmith can be used to prevent unauthorized use of artists' work by AI giants such as Midjourney and Stable Diffusion.

Wait, what? We're talking about AI?

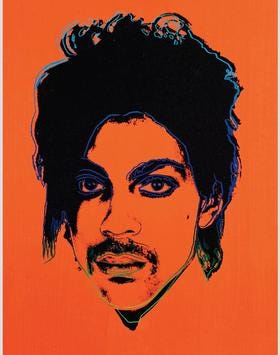

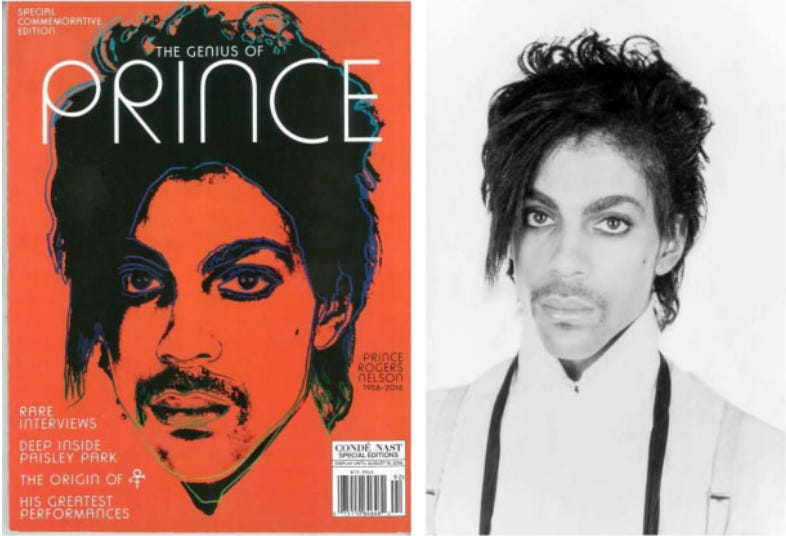

AWF v. Goldsmith is a narrow ruling that speaks only to the kind of reuse undertaken by AI companies and entitled art foundations. The Court says nothing about the original artwork. The majority goes to great pains to distinguish (a) Warhol's artwork from (b) a copy on a magazine cover, clearly, repeatedly reminding the reader that we're only talking about a single magazine cover.

Contrary to 99% of the headlines you'll read, the decision has nothing to say about the original artwork. The decision only addresses The Andy Warhol Foundation's decision to license a reproduction of Orange Prince to Conde Nast Publishing for use on a magazine cover in exchange for a $10,000 fee.

Yes, that's right. The Foundation (which we are not at any point going to call "Warhol," like its a human person - see Day 2 and Day 5):

licensed a reproduction of an appropriation artwork to a major corporation for a huge fee,

declined to pass part of that fee onto the independent artist whose underlying work formed the basis of said appropriation artwork,2 then

proactively asked a court to say its behavior was OK under fair use.

Tech interests made similar arguments to address concerns about the use of individual artists’ artworks in the training and creation of AI images. In fact, AI creators proceeded on the assumption that the Court would deem their activities fair use.

Here’s a spokesperson for Stability AI: “anyone that believes that this isn’t fair use does not understand the technology and misunderstands the law.”3

Well, Spokesperson Friend, the law has been clarified, and your team was a little overconfident. Sneering entitlement is never a good look for anyone!

AWF v. Goldsmith asks us what the defendant is trying to DO with the artwork. Not aesthetically, but practically. The opinion zeroes in A Truth Universally Acknowledged by contemporary art historians: the nature of an object’s purpose and meaning may change with a change in that object’s context.4

Here’s why that’s a good thing: the ruling zeroes in on the kind of use (i.e., unlicensed digital copying for a purpose that obviously supersedes the original) made by AI image creators that scrape to learn and create.5 Yet, it leaves more common human uses open to further interpretation.

The Court explains that Orange Prince might be deemed fair use or infringement under different circumstances.6

Want to make an appropriation artwork in The Factory? Have at. That’s one kind of use, and probably fine.7

Want to sell that Artwork to a billionaire? That is also probably fine.8

Want to license a copy to a corporation for a magazine cover and refuse to pay the photographer who created part of the work part of the fee? Nope, that’s not OK.9

The Court only addressed the last scenario, and openly, repetitively limited its analysis to one use and one context. To repeat myself, because I want you to care about this: that’s the scenario that matters when it comes to AI.10

Right now, you might be feeling annoyed. If everything is so context-dependent, then the Court made fair use more confusing. The “expert” who promised to explain all this in plain terms is happy about this?

It’s really not that confusing. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, the last Court case on fair use, was pretty easy to understand. Sotomayor’s opinion links back to Campbell and draws a straight, clear path to the 21st century by reminding us what fair use really is and how it works.11

Misapprehension #2: Fair use is a right just like free speech or the right to vote.

Kinda, but not exactly. Fair use can be described as (1) a right or (2) a defense to wrongdoing. In reality, it’s both.

Copyright and fair use are rights bestowed onto us by our legal system; these rights can be modified, repealed, and restrained.

For the newbies, let’s have a quick explanation of both.

Copyright is a form of protection grounded in the U.S. Constitution and granted by law for original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression.12 Copyright scholarship is a complex, niche area that blends legal studies, history, philosophy, and direct analysis of creative works. There are many competing theories that explain how, why, and when copyright became a legal right.

Fair use is one of the exceptions in copyright which allows use of copyrighted materials without obtaining permission. There are also many competing theories that explain how and why fair use works. What’s agreed upon by all: Fair use is a four-part, fact-specific legal balancing test. A court looks at the facts, context, and impact of every individual reuse, and assesses each use by four different measures - purpose, nature, amount, and market harm.13 To understand more, I recommend The Cyberlaw Guide to Protest Art as a starter pack.14

Technically, fair use operates as a defense to alleged wrongdoing. It can be extremely helpful to think of fair use as a defense as you’re trying to (a) understand a case or (b) decide if your own reuse would be characterized as fair use.

Lawsuits proceed according to very specific rules. The plaintiff and defendant take steps and make arguments in hyperspecific order according to the Rules of Civil Procedure. A defense can only be asserted in a specific way, at a specific moment in the timeline. Thus, there are limited ways to trigger the balancing test.

Like the rules of hair care, the introduction of a fair use defense is simple and finite.15 There are only two ways to do it; either:

(1) a defendant is accused of infringing someone else’s creative work OR

(2) a potential defendant files for a “declaratory judgment” (a court judgment that determines the rights of the parties without ordering anything be done or awarding damages) of non-infringement based on fair use.

Misapprehension #3: Lynn Goldsmith sued The Andy Warhol Foundation.

It was the other way around.

The popular understanding of the case seems to be that Lynn Goldsmith sued The Andy Warhol Foundation for infringement of her photograph. That would be scenario 1).

It may surprise you to learn that AWF v. Goldsmith kicked off with scenario 2). The Foundation proactively sought to have a court declare Orange Prince a fair use of Lynn Goldsmith.16 The Foundation kicked this dispute off. Goldsmith countersued, meaning she filed a legal claim as a reaction to a claim made against her.17

Misapprehension #4: Every Warhol is equally brilliant.

Kagan's dissent goes long with this one, equivocating Orange Prince with Marilyn (1964).18

Not everything I write is equally good. Not everything you draw is equally good. Not everything Warhol made is equally good. Orange Prince is not Orange Marilyn. New Portraits is not Canal Zone. Some of Picasso’s work is kinda crappy.

It's not transformative just because Warhol made it.

Appropriation is an artistic choice. In the 1980s, when Orange Prince was made, appropriation was a much more consequential choice than it is now.

From a legal perspective, stripping artists of responsibility for their choices relegates them to a diminished legal subjecthood. I have no problems with artistic consequences. Artists are not children. Artists are not insane (at least, not in the legal sense). Artists are not incompetent.

And yet, art historians called as experts, and those writing amicus briefs to support powerful defendants, frequently describe artists as incapable of accounting for their choices. I find this orientation bizarre, because it inevitably produces a result that these extraordinarily brilliant scholars can’t possibly intend.

When art history and intellectual property overlap, behavior that would be characterized as exploitation and repression in any other field is excused by “genius.” In the art world, geniuses tend to be white, male, and wealthy.19 When we repeatedly excuse legally questionable behavior on the basis of “genius,” we repeatedly excuse the legally questionable behavior of a small cohort of white, male, wealthy legal subjects.

For 30 years, fair use jurisprudence has encouraged an elite cohort of “geniuses” to see everyone else’s creative output as their “raw materials.” Judges, lawyers, and art experts have encouraged us to divide creators into castes: (A) the “geniuses” who make use of “raw materials” are allowed to take whatever they like, because they know best and (B) the producers of “raw materials,” who have no claim to their property and culture once a genius takes an interest.20 If that sounded so colonialist that it made you throw up a little in your mouth, then we’re on the same page.21

I don’t think this framework is what the art experts intended to produce, but it’s what we got.

For the last 30 years, fair use jurisprudence has repeatedly expanded the reach of already-powerful artists, with less just effects for less-powerful artists. Legal scholars and art historians talk about the impact of fair use cases on artists as if all artists are equal, or as if legal rulings concerning Jeff Koons and Richard Prince have a trickle-down effect on Etsy print sellers. All legal subjects should be treated equally under the law, but equal treatment is a fiction that blankets all areas of jurisprudence and obfuscates the truth: wealthy and powerful legal subjects have more access to justice than the rest of us.

AWF v. Goldsmith is an important step back from transformative use, but it’s also a step towards transformative justice. The anointed geniuses will be fine; they’re already rich, powerful, respected, and overrepresented. What we need is fair use for the 99%, and that’s exactly what Sotomayor and Co. improbably delivered.

To build a more just vision for fair use, we need to ask:

Who stands to benefit from an assertion of fair use?

Who will be characterized as mere “raw material”?

What are the consequences of our work?

What possibilities does our work serve?

What power structures is our work holding up?

Tomorrow, we dig into the “who”s, beginning with The Andy Warhol Foundation. In the next installments, I will address the specifics of the opinion, concurrence, and dissent in detail. I will keep asking the five questions above, and we will use these questions to consider the possible short- and long-term impacts of AWF v. Goldsmith.

You can read the whole opinion here: Andy Warhol Foundation For The Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al. If you’re not a lawyer or legal scholar, I strongly recommend you start with Gorsuch’s concurrence. The opinion and dissent talk to each other, quite dramatically at times. The concurrence steps outside the fray and outlines some key legal concepts in the tone of a patient elementary school teacher.

The Foundation could have paid part of the fee to Goldsmith? Absolutely! This story could have gone that way. You should have questions about this point; be patient for Day 2.

Kagan’s dissent is an Art History 101 class. Sotomayor, by contrast, is holding a 301 seminar on the dialectics of meaning. I’m deliberately avoiding deeper discussion - for now. We’ll cover the history of appropriation art on Day 5, when I savage - excuse me, assess - Kagan’s dissent.

Professor Daniel Gervais explains it all: https://www.theverge.com/23444685/generative-ai-copyright-infringement-legal-fair-use-training-data

Existing federal circuit and state court cases speak to different contexts. Many interested persons hoped the Court would resolve all potential uses in AWF v Goldsmith, but they (IMHO, wisely) declined to do so.

I am now waiting for an onslaught of whataboutisms. Lawyers would be out of work if not for “what about [this slightly different circumstance].” I “what about” for $350/hr. Inanity tries my expensive patience (especially when I’m explaining complex things for free) so read the Comments Policy before lobbing your hypothetical at me.

Id.

Id.

There is so much to say about AI. My favorite take on the subject, which is a great companion read to this essay, is Sarah Chappell’s “AI Is Not Knowledge Work’s Existential Threat,” especially the penultimate paragraph on true transformation.

I will dig into Campbell and later cases more deeply on Day 5.

This is the Copyright Office’s definition: https://www.copyright.gov/help/faq/faq-general.html

It’s a little old and oddly named, but I still find that Jessica Yurkofsky’s illustrations help my Art Law students grasp the concepts more quickly than any other free resource.

If you want to understand each factor, see Yurkovsky and Friends.

No, I didn’t mean to say “compare.” I meant “equivocate.” It’s a deceptive and misleading comparison that shouldn’t persuade you.

Data on art museums and markets incontrovertibly demonstrates that most recognized “geniuses” are white and male. Please what-about me on that. Talking about the minority of globally-recognized, non-white, she and they geniuses is my jam.

I go into this extensively in the June 2023 issue of Panorama. In the meantime, this is a great read on "raw materials": Andrew Gilden, Raw Materials and the Creative Process

That’s the truth bomb. If you’d like to know why I opened my own law practice instead of pursuing a career in academia, it’s because I say things like this IRL to people’s faces.

This is delightful, can't wait for the whole series!