Sedlik v. Kat Von D: Tattoos, Fair Use, and Fan Art

Customs and community norms matter, especially when a third of the jury has a tattoo.

Fair use cases decided after Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith have started making their way through the system!1 Friday gave us three big cases with divergent outcomes to chew on: Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg, McNatt v. Prince, and Graham v. Prince.

We don’t have judicial opinions to pick apart since 1) Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg was decided by a jury and 2) McNatt v. Prince and Graham v. Prince were settled. However, we know that Kat Von D won her case in a jury trial with a determination of fair use, and Prince was tagged with infringement in a pair of consent judgments.2

This is the kind of diversity that some see as “confusing,” but I consider “compelling.” So I don’t wear you out, let’s start with Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg and take on The Prince Cases later this week.

Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg:

Quick and Dirty: The issue at hand was whether Kat Von D’s use of Jeff Sedlik’s photographic portrait of Miles Davis as the reference image for a realistic tattoo was a fair use. The jury decided that Von D’s tattoo was a fair use of Sedlik’s photograph.

Why We Should Care: The case merits attention because Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg directly impacts aesthetic possibilities for a huge body of American legal subjects: according to the Pew Research Center, 32% of Americans have at least one tattoo. Had the jury decided against Von D, tattoo artists could be required to create only custom designs, seek cumbersome licenses for their work, or subject their clients to awkward consequences.

Plus, any overlap between tattoo art and copyright law creates a collision between money, bodily autonomy, and free speech, and that’s just fun.

Here are the spiciest parts of the case:

“Nobody ever asks for permission.”

Custom and culture tend to matter more than blackletter law when it comes to artistic practice. The habits of your peers are more likely to inform your decisions (and sometimes, your lawyer’s advice) than the actual text of the Copyright Act. Think of it this way: if you’re driving along and haven’t seen a speed limit sign, how are you supposed to decide on a safe rate of speed? By paying attention to the flow of traffic and other drivers’ MPH. The same thought process applies here. Most artists don’t spend their days reading the latest copyright opinions. Instead, they observe friends and mentors, ask questions in their communities, and flow with the intellectual current.

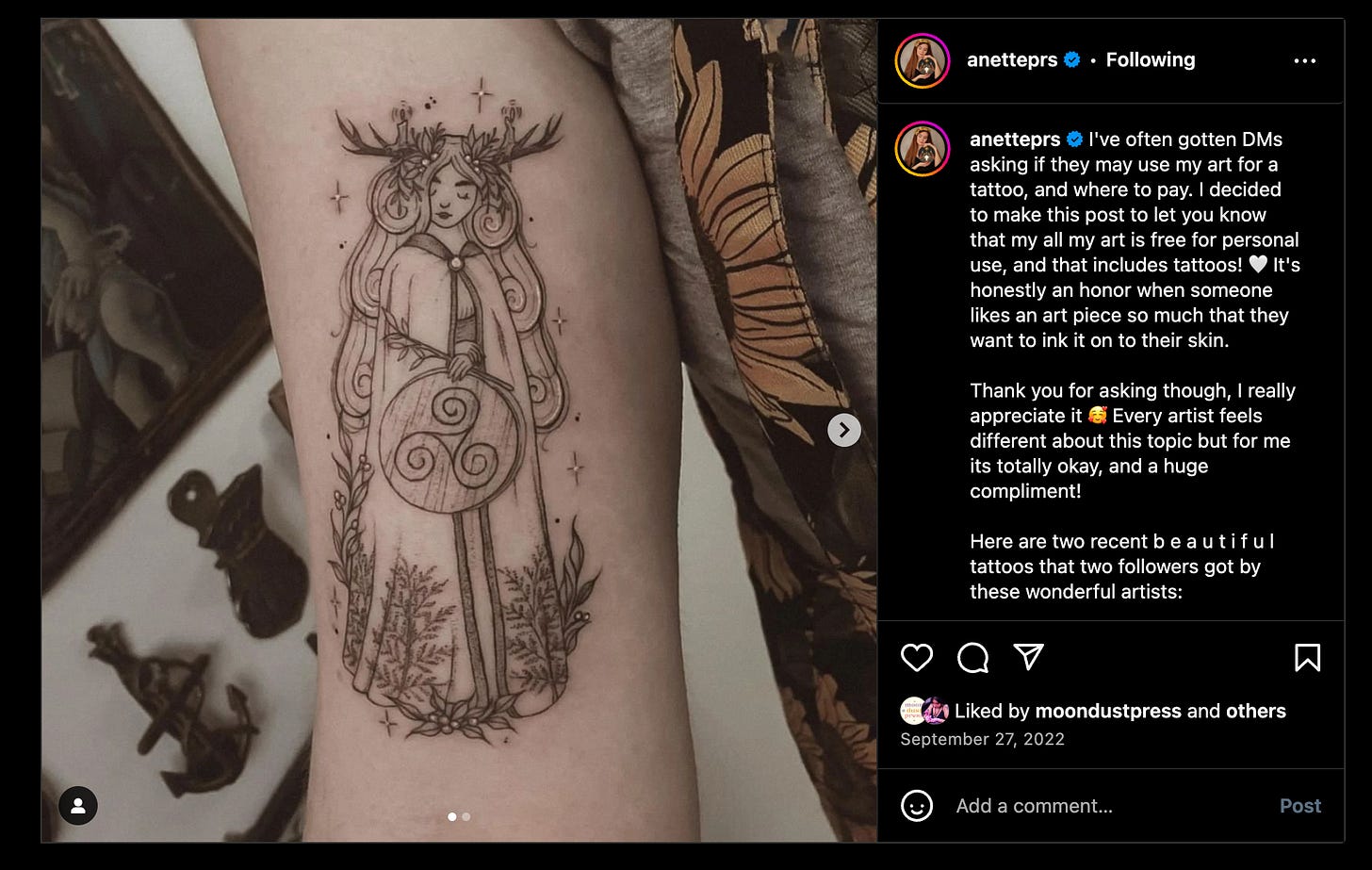

In her testimony, Von D averred that she has never asked for permission or obtained a license for a reference photograph. Furthermore, she stated she doesn’t know another tattoo artist who has, either. That appears to be generally true.3 However, younger artists are developing a more robust culture of attribution and remuneration. Artists whose work serves as frequent inspiration have developed ways to get paid or use reproductions to increase awareness of their practice. For example, Etsy returns thousands of results for affordable “tattoo tickets” that run $25 - $35. Some artists, such as Anette Pirso, are happy to have their work reproduced without payment. Others, such as Micah Ulrich, encourage fans to buy a print or make a nominal payment.4 And others, such as Kim Krans, collect tattoo “stories” via their websites.

Was Sedlik then asking to receive a $25 kickback for the use of his photograph when Kat Von D herself didn’t charge for the Tattoo and hasn’t charged for any tattoo since 2012? Not at all; his team took up a legally-attenuated-but-culturally-fascinating line of argument: Sedlik posited that Von D tattooed her friend Blake Farmer for free, but the tattoo, and the Instagram post that featured it, were a brand promotion for Kat Von D’s money-making ventures: her “tattoo parlor, an art gallery, a cosmetics company, a clothing company and a shoe company, among other businesses.”5

This is known as contributory infringement - if a person does not directly violate a copyright but induces or authorizes another person to directly infringe the copyright, they may also be liable. (Contributory infringement is how an appropriation artist and her gallery are both sued - the gallery is accused of inducing or authorizing the artist.) Here, Von D’s own successful businesses were characterized as “inducing or authorizing” the artist to create a free tattoo to increase publicity and drive sales.

But, as long as we’re considering contributory infringement, doesn’t that mean the client is liable for contributory infringement, too? In practice, tattoo artists are rarely given free rein. Clients bring artists their ideas and often supply the visual reference. (Read about an example here.)

These are robust arguments for future plaintiffs to pick up when filing claims against influencers, and I expect to see them over and over again in the next few years!

It’s Fan Art

In her testimony, Von D pressed upon the characterization of her work as “fan art.” She said: “I'm literally tattooing my friend with his favorite trumpet player because it means a lot to him and I make zero money off it, so I think there's — I'm not mass-producing anything or gaining any monetary value, so I think there is a big difference. It’s fan art.”

When asked to elaborate, Von D continued: “Sure, people do it all the time…In my past, yeah, I’ve done Nicole Richie’s rosary on her ankle, Britney Spears’ cross on her stomach, Drew Barrymore’s sunflower, Angelina Jolie’s Thai stuff, the Pam Anderson arm bands, those are all iconic celebrity tattoos that so many people get them to pay homage to them. It’s fan art. That’s what we do. That’s all tattooing is.”

Von D’s testimony had the paradoxical effect of undermining her specific defense yet justifying other artists’ work. Evidently, the jury bought her self-identification as a “fan” of Sedlik’s work, but that’s not really what Von D and her human subject, Blake Farmer, said. Both the tattoo artist and her walking canvas identified themselves as fans of Miles Davis not fans of Jeff Sedlik. Miles Davis has a body of artistic, copyrighted work and a protected likeness to admire.6 Jeff Sedlik has a distinct body of artistic, copyrighted work to admire. To be a fan of one is not necessarily to be a fan of both.

Furthermore, Von D did not mention Sedlik in any of her social media posts about Farmer’s tattoo. Did Sedlik truly want a license fee from Kat Von D, or did he want attribution? One wonders how Sedlik would have reacted if Von D had named and celebrated him. You know, as a fan might do.

Sedlik granted another tattoo artist a “retroactive license” for his use of the same Miles Davis portrait and waived his usual $5,000 fee. The difference? That artist had 3 Instagram followers and apologized to Sedlik. Money can be a balm for hurt feelings, but an apology can save you a lot of money.

Perhaps the receptive artists named above - Pirso, Ulrich, Krans - are lenient and encouraging because they feel appreciated. Perhaps they encourage fans to reproduce their work because the resulting stories and images - as recuperated and recirculated under their own banner and control - increase their visibility and sales.

Fans tend to spend money on and say nice things about the people they admire.

Bodily Integrity and Personal Expression as Fifth Factor

Von Drachenberg asked the court to consider a “fifth factor” in addition to the to the four factors of fair use: “fundamental rights of bodily integrity and personal expression.”7 A proposed addition to the four factors of fair use is not terribly interesting ( the four we have are problematic enough, thank you). However, this suggestion points to a gruesome possibility should Sedlik win on appeal: the Copyright Act allows a court to order the destruction of all copies made or used in violation of the copyright owner’s exclusive rights.8

Courts have issued such orders before - most notoriously when Judge Deborah Batts gave Patrick Cariou the option to destroy Richard Prince’s entire Canal Zone series in 2011.9 (The works were spared by the Second Circuit on appeal.) In other cases, such as Rogers v. Koons or the new Prince cases we will discuss in the next post, the defendant is prohibited from making, selling, lending, or displaying the infringing works, and the existing copies must be delivered to the plaintiff.10

Obviously, one can’t deliver a human forearm to a prevailing plaintiff, and tattoo cover-up or removal wasn’t contemplated by the authors of the 1976 Copyright Act. There’s actually a very good reason why tattoos weren’t considered by Congress: most states banned tattooing in the 1960s for public health reasons. The problems contemplated in Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg were inconceivable in the early 1970s.

Tattooing is a weird space in copyright not because there’s some inherent opposition between free expression and intellectual property but because tattooing wasn’t viewed as artistic expression during the last revision of the Copyright Act. The art form was viewed as a public health peril.

It wasn't until the 1990s that artists and their subjects successfully re-characterized tattoos as a form of expressive speech, allowing ink entrepreneurs to flourish. However, health codes are municipal, so it took decades for tattooing to become the widespread, normative practice described in this case.

It’s hard to have black-and-white rules for expression because copyright is historically situated.

In Summary

Is this only for tattoo art? Is Sedlik applicable beyond tattooing friends for free? how broadly relevant is this case?11

What can artists reasonably take away from Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg?

Customs and community norms matter. Statutes and Supreme Court opinions may suggest an obvious outcome, but that outcome may be conditioned on the usual behavior in the market. Know what’s normal for your medium.

Cite, celebrate, attribute. Asking nicely, name-checking, and saying you’re sorry if you forget can save your reputation and your bank account.

Copyright is historical and contextual. We don’t (and can’t) have easy-to-follow rules for all circumstances because progressive people like artists are constantly changing the game. ;)

Thanks for reading! If you have any specific questions about Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg, comment below or send me a link at hello@implementlegal.com.

— THE READING LIST: FAIR USE CLASSICS —

I’m preparing to present at a conference, so I re-read lots of old reference material this month. Here are some classics from my archive. Pick your rabbit hole!

Is Richard Prince the Andy Warhol of Instagram? (New York Magazine, 2016)

This did not age well. Full of astounding quotes from Prince that don’t read the same after #MeToo. A personal favorite: “It’s like sometimes I feel I’m fucking what I’m looking at.” This man made “Spiritual America.” Cringe.

Beebe v. Rauschenberg: The First Big Appropriation Lawsuit (greg.org, 2014)

Greg Allen is a gem, and this is the article that first made me think deeply about the “emotional, economic, and power complexities” inherent to copyright disputes.

Art Rogers v. Jeff Koons (Design Observer, 2008)

A rich narrative history of a complex case that involved the kind of injunction found in McNatt v. Prince and Graham v. Prince. This one aged beautifully; it’s full of tiny facts and great quotes, and it reads like a novella.

The cases discussed below were filed years ago but a) were reconsidered to incorporate the Supreme Court’s determination or b) simply took that damn long. These respond to AWF v. Goldsmith, but the photographer plaintiffs weren’t influenced by the Court’s decision for Goldsmith.

Many journalists are erroneously referring to the result as a “ruling,” which it’s really not - the parties figured it out on their own and the court cemented their agreement. I’ll explain the mechanics of verdicts, rulings, consent judgments, and private settlements in the next newsletter. Alternatively, never-erroneous Marion Maneker gives a brief explanation in lay terms here (see Notes section, #3).

Guess what I always do while getting inked? Ask the artists what they think about licensing.

Ulrich features reproductions on his feed and stamps out the same comment under every post: “While I don’t do any tattoo stuff - I don’t mind folks getting my art inked, I just ask that anyone who wants to get it done considers picking something up from my online shop or purchasing a tat flash to help let me keep making my art! Thank you all so much for your support! ❤" If you want to know what a “perfect” instruction for use of your artwork looks like, look no further.

Sedlik Complaint, Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg, p5.

Where was the Miles Davis estate in all of this, anyway?

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/503

Cariou v. Prince, 784 F.Supp.2d 337 (2011), 355.

Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301, 306 (2d Cir. 1992). I’ve always wanted to know what happened to the fourth copy of “String of Puppies.” Is it still in a warehouse? Do tell me!

Technically, it’s only applicable to California artists, but judges from other states use persuasive precedent to address niche subjects like tattoo art. Frankly, all visual art is still considered niche in most courts!

I appreciated this so much. I had an issue come up recently about someone sharing my work that I'm still chewing on. Not just the legality of it - and I don't actually know the true legality of it if I'm honest, but the diplomatic way to word things. How can we point things out kindly, fairly, with good boundaries, educate folks who honestly might not have thought through their actions, and not engage that old game of defensiveness before it becomes a hostile situation? Your writing helps artists in all of these areas. Thank you for what you do.