Cultural Heritage, Black Mountain College, and the Future of the River Arts District

Do or die. Literally.

For decades, North Carolina artists have been preserving Appalachian cultural heritage in profoundly egalitarian collectives, but Hurricane Helene put it all at risk.

If you watch any kind of prestige TV, you can understand this week’s installment as a “bridge episode.” A bridge episode has less bombastic action but gives you essential information that drives the plot forward. King’s Landing is the center of the action, but you have to visit The Wall if you’re going to see the bigger picture and understand what’s at stake.

Our version of The Wall or Númenor is the academic concept of “cultural heritage.” This capacious term describes the range of traditions, values, and art forms passed down through generations within a community. Cultural heritage isn’t static; it forms a bridge between the past and the present. It evolves as individuals try to maintain a sense of identity and continuity in a rapidly changing world.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) protects and promotes cultural heritage at the international level through conventions like the World Heritage Convention and the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. However, UNESCO isn’t coming to save Western North Carolina’s cultural heritage — not because it isn’t worth saving, but because a string of United States presidents effectively burned that bridge.

Western North Carolina must preserve its own traditions, values, and art forms. The nature of artistic practice in the region — transgenerational, land-based, craft-driven — makes this a particularly challenging project. Yet, the nature of artistic practice area region — collective, interdependent, recuperative — gives me hope.

Key Takeaways

📌 Cultural heritage is defined by the person or entity with the power to write the definition.

📌 Intangible cultural heritage is preserved through continual practice; it has to be done to be preserved.

📌 The Western North Carolina arts scene is driven by artist collectives who preserve intangible cultural heritage.

📌 “Cultural amnesia” is a real possibility in the River Arts District.

Who Owns the Past?

The art historians are rolling their eyes. Every conference in the field has at least one panel titled “Who Owns the Past?” And yet, the question’s ubiquity is proof of its enduring utility and importance. We must keep asking because who matters more than what, when, how, or why when we’re talking about cultural heritage.

For art historians, cultural heritage is about preservation, knowledge, and access. First, art historians ask how we can best preserve objects for future generations through conservation and, controversially, location. Second, they seek to index the information surrounding the object, whether historical, scientific, cultural, or aesthetic. Third, they try to ensure that the object is accessible to scholars and museum visitors. However, as the Harvard Department of Art and Architecture explains, a dislocated and globalized approach to preservation has its limitations:

This framework is certainly valuable; however, it has also been used to justify the acquisition of unprovenanced items by museums and private collectors, who buy into a Eurocentric and saviorist paradigm which positions the (often) colonial Western museum as a more suitable guardian of a cultural inheritance than the society from which it originated in the first place.1

Thus, Harvard adds a fourth consideration: the social, cultural, spiritual, and aesthetic importance of the object or site to the people to whom it originally belonged.

This fourth consideration is important because it prioritizes the concerns of the specific group of human beings who originated the cultural heritage site or objects and might, you know, like to stay intimately connected to their heritage. Over the last three centuries, “heroic” acts of cultural heritage “rescue” have been undertaken when sites and objects were considered vulnerable to neglect, decay, and destruction due to environmental factors, human negligence, or deliberate acts. However, some of these “rescues” might be better characterized as “looting.” (*cough* the Elgin Marbles *cough*).

When advocating for the preservation of cultural heritage, entities like UNESCO and Harvard tend to broadly categorize human-made objects and sites as tangible and intangible.2

Tangible Cultural Heritage

Art historians tend to focus on tangible cultural heritage — physical artifacts produced, maintained, and passed down over generations. In the fine arts and architecture, tangible cultural heritage includes (but is not limited to) paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, buildings, and monuments. Tangible cultural heritage may also include buildings, monuments, and books considered worthy of preservation. Museums, galleries, and archives play crucial roles in maintaining these artifacts for present-day scholarship and for future generations. Physical objects that we can see testify to the ingenuity and creativity of past generations. These objects help us tell a story of the people and the eras they come from.

Helene washed away plenty of tangible cultural heritage. This is tragic, but knowledge of these works, the skills needed to make them, and the stories of their makers can be preserved. Western NC’s greatest strengths are found in its intangible cultural heritage.

Intangible Cultural Heritage

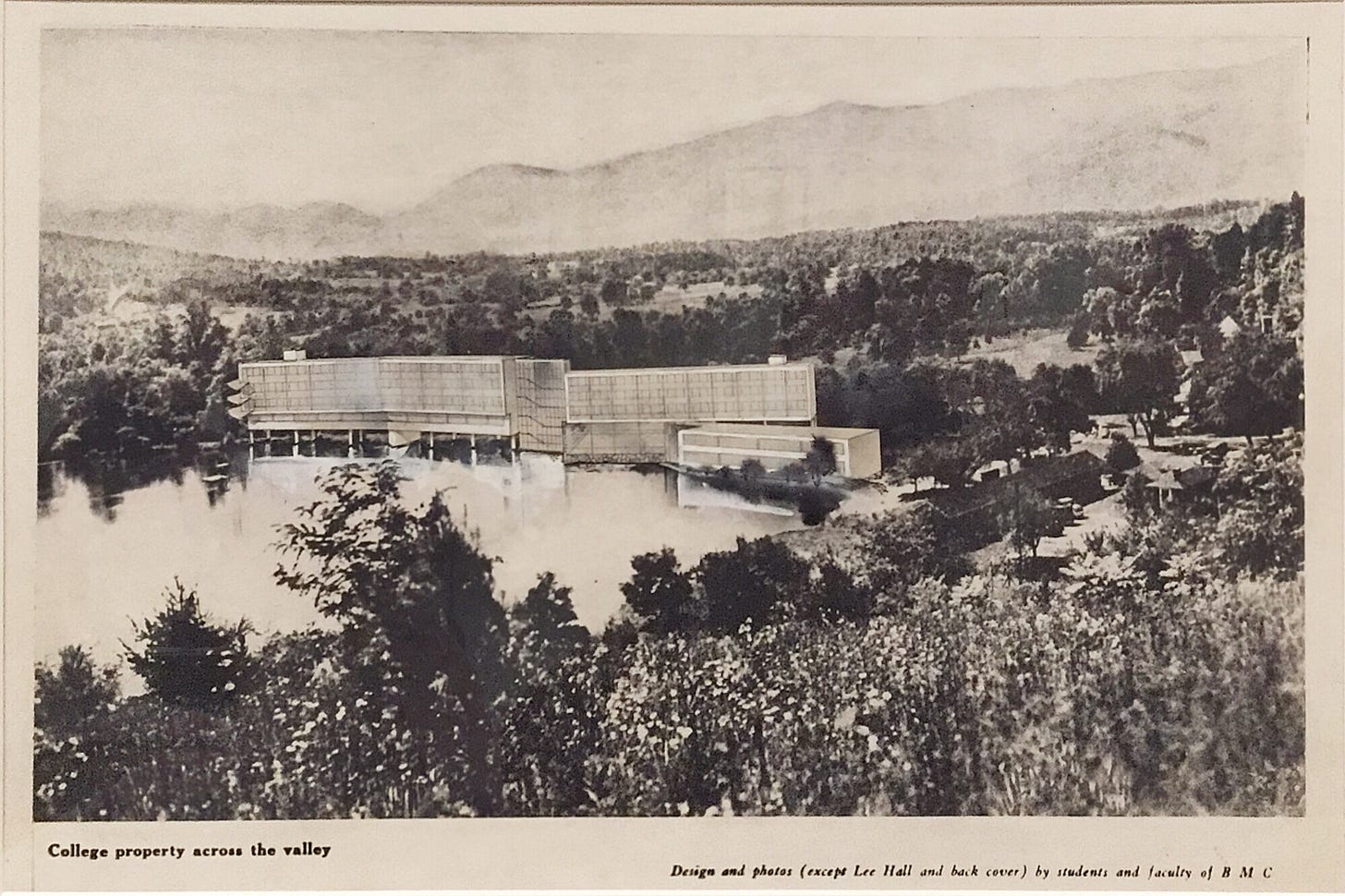

Intangible cultural heritage is sometimes called the “living expression” of culture. It encompasses practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills, music, dance, theater, rituals, festivals, and traditional craftsmanship. We may also define a cultural space as intangible cultural heritage if that space is more residual than actual (e.g., the former campus of Black Mountain College, a location that is now primarily used as a summer camp).

On a more personal level, intangible cultural heritage may include songs, recipes, ceremonies, traditions, and dances passed down through generations. For example, my grandmother’s recipe books are tangible cultural heritage, but the recipes themselves — which are burned into my brain and muscle memory, and have been uploaded to a cloud server so that the whole family may share them — are intangible cultural heritage. Intangible cultural heritage is just as important as tangible heritage because it reflects the practices, representations, expressions, and knowledge that enable cultural communities to maintain their sense of identity and continuity. Unlike tangible heritage, intangible heritage is preserved through continual practice and transmission from one generation to another. It has to be enacted to be preserved.

⚡ Unlike object-based cultural heritage, intangible cultural heritage must be enacted — or it is lost.

Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story

“Intergenerational transmission” is a fancy way to say “telling stories.”3 Various organizations worldwide work to identify, protect, and preserve cultural practices and the spaces where these practices are aimed. These efforts aim to preserve the history and traditions of different cultures and promote respect for cultural diversity and human creativity. But these efforts can also be called “looting,” “colonialism,” and “exploitation” when powerful interests are prioritized over the concerns of the originating culture.

Identity and Motivation

What defines the difference between the “rescue” and “exploitation” of cultural heritage? Generally, a storyteller's identity and her motivations for writing the narrative the way she does. Author and artist Oliver Jeffers said this about climate change and stories in last Sunday’s New York Times:

All we are as people is a collection of stories — those we are told, those told about us, those we tell to ourselves and others. They explain our identity and express our values, and they’ve long shaped societies — Sparta as a culture of warriors, America as the land of the free and so on. But when several conflicting stories are being told, they can also limit us, delude us and divide us. Too often they suit only the teller, not the audience.4

As Jeffers explains, the stories we tell today are foundational to who we become tomorrow. By attending to the impact of climate change on cultural heritage, we safeguard the past — and shape the future. Cultural heritage programs ensure that stories continue to be shared and traditions endure.

But the storyteller's identity matters, because his motivation matters; his goals shape the story — what’s left in and what’s left out. All too often, the storyteller is simply a participant with the most financial resources, not the most cultural investment. That kind of storyteller isn’t invested in the community’s shared history; he’s interested in shaping the next chapter to flatter himself.

To elaborate on this point, a brief history of UNESCO and the United States.

Our Fraught Relationship with UNESCO

At the international level, UNESCO defines and advocates for tangible and intangible cultural heritage. UNESCO was established on November 16, 1945, in the aftermath of World II to foster peace. Its founding principle was that politics and economics are not enough to secure lasting peace; peace must established based on moral and intellectual solidarity. (To really boil it down: “If we can all agree that bombing churches and museums sucks for everyone, maybe we won’t do it again. Cool? Cool.”)

The US was a founding member, but its relationship with UNESCO has been marked by complex interactions and withdrawal periods reflecting broader tensions in international relations. Disagreements around media representation and perceived politicization first began to surface during the Cold War. In 1984, the United States withdrew from UNESCO, citing concerns over mismanagement, corruption, and perceived bias against Western countries, particularly in policies related to Israel.5 After that, the US was absent from the organization for nearly two decades. The US rejoined under the Bush administration but cut off funding in 2011 when UNESCO voted to include Palestine.6 The US withdrew once more in 2017, citing “mounting arrears at UNESCO, the need for fundamental reform in the organization, and continuing anti-Israel bias.”7 It rejoined under the Biden administration in 2023.8

Why does the US keep ditching out? Well, when UNESCO was created in 1945, it was a Western entity funded by Western countries with an angle. The Allies wanted World War II taught in a certain way, especially in European schools, and UNESCO was the way to shape school curricula. During the Cold War, the US also saw UNESCO as an anti-communist advocate for democracy and free speech. When the US left UNESCO in 1984, UN Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick said bluntly: “The countries which have the votes don’t pay the bill, and those who pay the bill don’t have the votes.” By “votes,” Kirkpatrick meant “influence over the global narrative.” When it paid the bills, the United States expected to be given editorial powers over global history; when that didn’t happen, the US took its checkbook and left.

The editor’s identity matters when history is the narrative. If the artists are in charge of the story of recovery, Western North Carolina will be fine. If not, we may see a vast creative exodus from Asheville and the surrounding areas.

Let’s understand why identity is so important to Asheville’s cultural heritage.

The Cultural Heritage of Western North Carolina

What is the cultural heritage of Western North Carolina?

From the earliest Native American inhabitants, Appalachia has been a cradle of artistic expression. Indigenous peoples of the region crafted exquisite beadwork, pottery, and basketry, infusing practical objects with profound cultural and spiritual significance, laying the groundwork for a tradition of exceptional craftsmanship and artistic expression that would endure for generations.

When European colonists arrived, a fusion of artistic traditions unfolded, resulting in a vibrant cultural mosaic of quilting, woodworking, metalworking, and weaving. The arts developed out of settlers’ need for durable goods while also serving as a canvas for personal expression.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, artists, writers, dancers, and musicians demonstrated reverence for the region’s storied past while weaving contemporary themes and techniques in new projects. The Works Progress Administration preserved and showcased Appalachia’s artistic heritage, underscoring its indelible contribution to the American cultural landscape. Appalachian folk music flourished, influencing the development of blues, jazz, bluegrass, honky tonk, country, gospel, and pop. The diaspora of Black Mountain College established a holistic model for contemporary artists working in experimental art.

Over centuries, the story of Applachia’s culture has been driven forward by artists' urges to reach back. Appalachian artists have always looked to their predecessors for wisdom, recuperating and preserving skills that might otherwise be forgotten in the relentless march of modernity. The global art world appreciates the aesthetic fruit of these efforts but rarely understands the hard conditions from which such beauty grows or the necessity of place in these traditions.

For example, Black Mountain College.

Black Mountain College and the Dream of Utopia

Black Mountain College (BMC) was a brief yet iconic moment in the history of art. It is understood as a utopian project in non-hierarchical holistic learning, where artmaking was central to a liberal arts education and every aspect of life was experimental and interdisciplinary. That’s all true, but few people understand how rural, rustic, and rickety the college really was.

Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Ruth Asawa didn’t matriculate into the resort-like environment students experience at Duke and UNC. Many artists were handed a hammer on arrival because they were expected to build their studios themselves. Food was scarce because the school depended on its farm to feed its faculty and students. That sounds terribly romantic, and the farm eventually thrived, but “hot dog soup” was still served regularly.9

The BMC property was later purchased and converted to a Christian summer camp, but it remains home to the Lake Eden Arts Festival (LEAF), a family-friendly version of Burning Man, and Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center’s {Re}HAPPENING, which is kind of like a Ren Faire for BMC groupies.10 That’s meant lovingly. As executive director of Black Mountain Museum + Arts Center (BMCM+AC), I canceled the 2016 {Re}Happening because Camp Rockmont raised our event rental rate by more than 600%. I told them to fuck off and held a street festival in downtown Asheville instead. This was arguably more in line with the spirit of BMC than any prior {Re}HAPPENING, but the crowds did not go wild.

What I learned from this experience: {Re}HAPPENING is fundamentally a pilgrimage to BMC land to recreate specific historical moments and experiences. It’s more akin to a Society for Creative Anachronism event than a contemporary arts festival. That’s not a dig; it’s a critically important observation if we’re trying to understand BMC's cultural impact, Western NC's draw for contemporary artists, and the organization of artists’ collectives in the 21st century — i.e., the intangible cultural heritage of Western NC.

Creative Anachronism and Artists Collectives

Creative anachronism is central to the success of the Western NC art scene. For the last 20 years, Asheville has conducted an extended inquiry into what Portlandia called “The Dream of the ‘90s.”

Artists flock to the mountains for myriad reasons, but the central theme I’ve noticed is identity-based affiliation. Some local artists grew up in the mountains, but most came to Asheville as adults, seeking a specific experience that is hard to achieve in 21st-century New York City or Los Angeles (and, now, Portland). Inspired by collectives like BMC, thousands of artists have organized into hundreds of collectives dotted through the hills and valleys of the Blue Ridge mountains. Like the BMCM+AC supporters who convene at Lake Eden every Spring, these artists have made a pilgrimage to be with like-minded fellows on hallowed land. Remember, the throughline of Appalachian culture is the urge to reach back. In Western North Carolina, this is not expressed as appropriation but as affiliation.

Artists opt in to Harvard’s fourth consideration, adopting the identity of “Appalachian artist” and forming collectives based on similar values and shared resources.

Asheville artists are not recruited by ambitious gallerists, and they do not seek to climb strict social hierarchies. They are drawn to the area by residencies at Penland School of Craft (another hallowed ground) or mentorship with singularly knowledgeable artisans. They are pulled close by their interests in traditional craft knowledge, revivals of the “old ways,” spiritual/aesthetic synchronicities, and the promise of communities that reflect their personal and artistic values. These artists cluster in creative coves in Spruce Pine, Marshall, and the River Arts District. They organize in collectives that share space, tools, and equipment. They market each others’ work. They teach other traditional skills like loom weaving, making dye from vegetables, creating clay from local creek beds, and advanced glassblowing techniques. These skills take years to master.

They teach each other traditional skills that take years to master.

For decades, North Carolina artists have been preserving intangible cultural heritage in deeply democratic ways. Artists gather at Penland, the Center for Craft, Treats Studios, the North Carolina Glass Center, Local Cloth, Art Garden AVL, and many other enclaves to share studios, kilns, and techniques. They teach each other, just as my grandmother taught me her recipes. They make online courses and share traditional knowledge with the world, the way I uploaded my grandmother’s recipes to the cloud.

But how will collective practices if artists cannot gather in the cultural spaces — for example, the studios flooded by the French Broad River — that facilitate their engagements? Without the structure and funding of a body like UNESCO, how can these groups remain intact and preserve these skills and secrets for future generations?

Cultural Amnesia

Scholars refer to the loss of cultural heritage as “cultural amnesia.”11

The term “cultural amnesia” is used to refer to the abandonment of tradition, heritage, community, and landscape that occurs when societies have their history and heritage manipulated and targeted by groups that have the ability to exert a certain sense of power and control over them.”12

This term is usually applied to the mass forgetting imposed by dictators or foreign regimes in the wake of genocide (e.g., the olives groves of Palestine), the restriction of sacred sites (e.g., most of Nepal), or the manipulation of historical facts (e.g., the 1989 Tiananmen Square Protests). Yet, given the nature and scope of Western NC’s cultural heritage — oral, distributed, and contingent on doing — I think fears of cultural amnesia are not overdramatic.

In Asheville, glassblowing artists congregate in groups at shared glory holes, ceramicists gather to produce their works in community kilns, and painters curate group exhibitions. When studios are washed into rivers, cultural spaces — the places where intangible cultural heritage is enacted and re-enacted — are lost. When artist collectives have nowhere to congregate, where will they make art?

⚡ When the campfire is banked, where do we gather to tell our stories?

Personally, I fear a mass exodus and the distribution of the Asheville craft knowledge network. When Black Mountain College closed, the world arguably benefited because the faculty and staff pollinated BMC’s ideals across the globe. But something essential about BMC was lost when the land was sold, and that lost heritage cannot be retrieved in an annual weekend jaunt. I don’t want the River Arts District to be a distant-if-inspirational idea for my daughter's generation. Budding artists are sitting in middle schools across the United States. A decade from now, they will leave home to seek their own utopian dreams. Will they be able to find artist mentors and creative communities in the hills and valleys of Western NC?

Next Week:

Next week, we’ll pick up the question of identity and ask, “Who gets to tell the story of Hurricane Helene’s impact on Western North Carolina?” UNESCO isn’t going to be the author or editor of this tale — the United States’ relationship with that body is too fraught. Will art historians get involved? Will the artists tell their own stories?

As promised, we’ll focus specifically on the story of the River Arts District and look at early responses from Asheville real estate developers. They are arguably a lot like the United States when it comes to cultural heritage—interested in controlling the narrative and hell-bent on telling a flattering story.

Harvard Dept. of Art and Architecture, “Whose Culture?”, https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/whoseculture

“Natural” cultural heritage is a thing, too, but it’s outside our purview.

Hamilton is Eliza’s story. Her highly edited version. https://genius.com/Original-broadway-cast-of-hamilton-who-lives-who-dies-who-tells-your-story-lyrics

Oliver Jeffers, “An Artist Rethinks Climate Change in Words and Pictures,” New York Times, October 6, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/06/opinion/climate-change-solutions.html

Olivia B. Waxman, “The U.S. Has Left UNESCO Before. Here’s Why,” Time, October 12, 2017, https://time.com/4980034/unesco-trump-us-leaving-history/

Formally, based on US laws that prohibit funding to any UN agency that recognizes Palestine as a state.

This story obviously concerns Israel and Palestine. But we are not—let me repeat—we are not going deep on Israel and Palestine here. We are embracing the not-hot take that the United States does weird and self-destructive things. Boosting from UNESCO is just one item on that long list.

Pamela Falk, “U.S. rejoins UNESCO: “It’s a historic moment!,’” CBS News, July 11, 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-rejoins-unesco-biden-adminstration-un-agency-historic-moment/

Nancy Zastudil, “The Farm at Black Mountain College You Didn’t Know Existed,” Hyperallergic, September 30, 2024, https://hyperallergic.com/954310/the-farm-at-black-mountain-college-you-didnt-know-existed-david-silver/

Harvard Dept. of Art and Architecture, “Cultural Amnesia: Can We Remember Not to Forget?” https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/whoseculture/cultural-amnesia

Harvard Dept. of Art and Architecture, “Cultural Amnesia: Can We Remember Not to Forget?” https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/whoseculture/cultural-amnesia

Like the snotty new director who sailed in from Duke and transplanted BMCM+AC’s signature event to downtown Asheville? I can own that. Alice, I’m sorry — I should have listened more and talked less. The quote is from Harvard Dept. of Art and Architecture, “Cultural Amnesia: Can We Remember Not to Forget?” https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/whoseculture/cultural-amnesia