“Climate Havens,” Asheville’s River Arts District, and Cultural Heritage

Asheville is a model for cultural sites in the age of climate disasters. What kind of model? That remains to be seen.

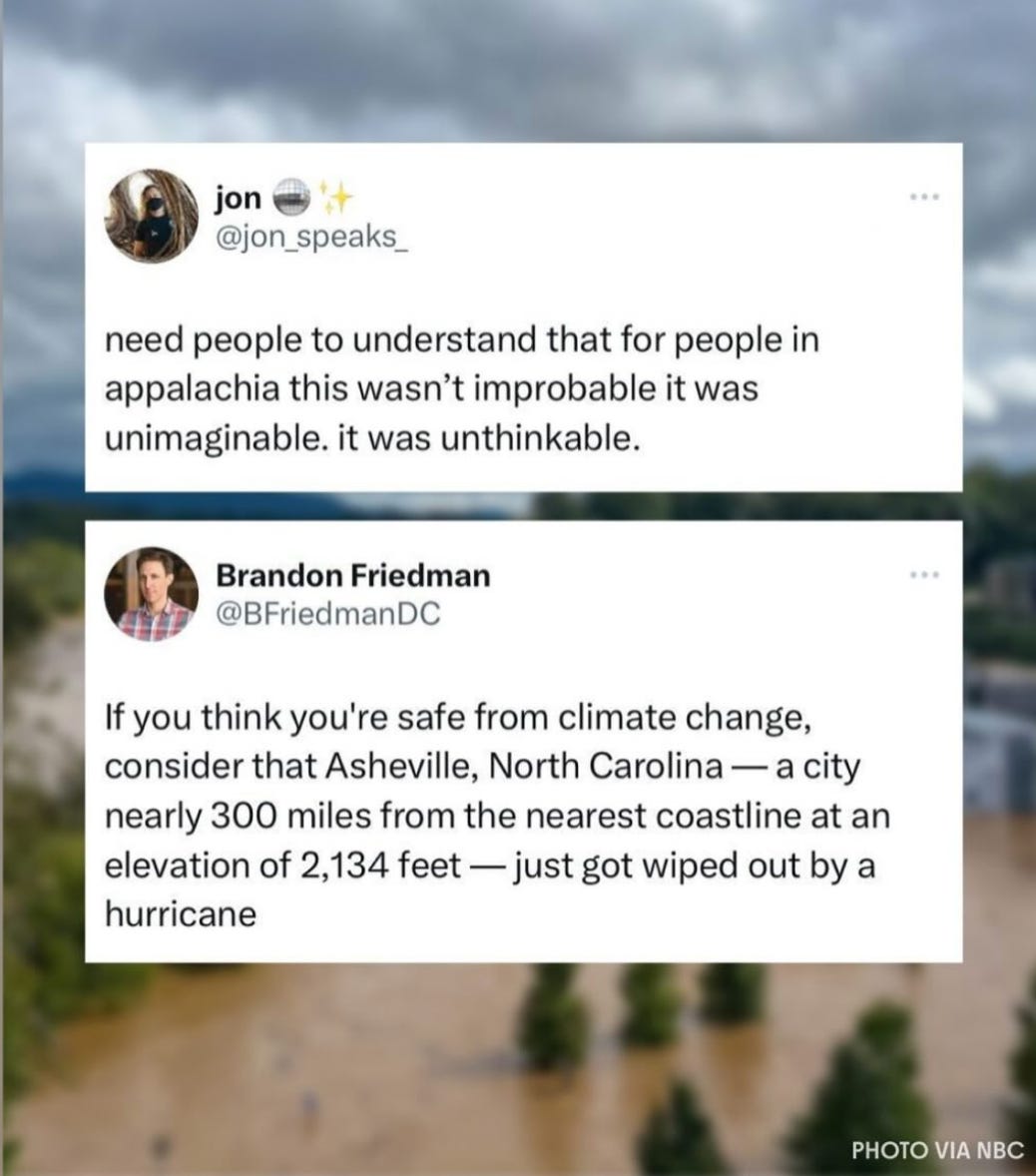

Asheville is a small town with a big cultural impact. It’s also my former home. Last week, Hurricane Helene practically destroyed it. Ironically, Asheville has been touted as a “climate haven” for years—a false promise that may have contributed to the scope of destruction. We can’t understand Asheville as a climate haven because no such thing exists, but we can—and should—understand the town and its mountain surroundings as a cultural heritage site. And we should use Asheville’s River Arts District as a model for the preservation and protection of cultural sites in the age of climate disasters.

⚡️ “Aha! Moment”: The catastrophic flooding in Western North Carolina is a humanitarian crisis and a cultural heritage disaster.

In this four-part series, I’m going to convince you that “climate havens” are bullshit, explain why Western North Carolina should be deemed a cultural heritage site, and suggest that the fate of Asheville’s River Arts District may model the impact of climate change on artists across the world.

In Part 1, I will explain why “climate migration” made the River Arts District an exceptionally vulnerable cultural space. (Today)

In Part 2, I’ll introduce you to the term “cultural heritage” and explain what it means and how it is applied by international bodies like UNESCO. (October 8)

In Part 3, I’m going to persuade you that the art and architecture of Western North Carolina deserve the kind of attention given to the post-Katrina French Quarter, European war zones, and Middle Eastern mosques. (October 15)

In Part 4, I’ll explain why our efforts to preserve and rescue our cultural heritage must increase in proportion to climate threats and decide that Western North Carolina is a test case we must take seriously. (October 22)

Let’s go.

Part 1 - Key Takeaways

📌 Asheville proves that there is no such thing as a “climate haven.”

📌 Asheville’s River Arts District was directly impacted by the climate haven fairytale.

📌 Artists everywhere are especially vulnerable to loss during periods of rapid economic growth.

What is a “Climate Haven”?

In 2018, Rolling Stone described a “great migration” from the coastal plains to the mountains, estimating that 50,000 climate migrants would move to Western North Carolina in the next 60 years, yielding a 15 percent increase in the size of the local economy.1 Realtors, developers, and city planners loved these stats and began pumping a false narrative that Asheville and its surroundings were immune to climate change. Mosaic Realty is one of the most prolific agencies in town. In the video above, owner Mike Figura said: “People have noticed and are moving here to escape wildfires, to escape floods, to escape hurricanes, to escape droughts.” (For the avoidance of defamation, I don’t think Figura and others knew this was a false narrative, but my Eastern North Carolina family instilled in me that rivers are never, ever safe.)

I know a thing or 12 about all this because I used to live in Asheville’s River Arts District. My law firm was born in a spare bedroom during the pandemic. I was a resident, part of the business association, and a North Carolina Glass Center board member. I had a front-row seat to the prosperous development along the riverside. Many of my clients still work in these buildings, and my friends live in houses on the hills above the French Broad River. Before we settled on Jefferson Drive, we read the stats and calculated the risks. We made the big investment, and when we renovated Asheville’s Most Exasperating Edwardian™, I learned that we had 100-year-old terracotta sewer pipes. During those years, I also learned a lot about the history of artist neighborhoods, and I worried that artists in the RAD would be quite fucked if Mike Figura, Scott Shuford, and their peers got it wrong.2

SoHo, the Pearl District, and the RAD

The River Arts District wasn’t located next to the French Broad River because that was a nice view from a studio window. The RAD was cheap because it’s in a floodplain. Artists tend to congregate in less desirable areas, sometimes in not-exactly-legal structures. That is, until they make the neighborhood cool. Then they are priced out by developers. For example, consider the lofts of New York City’s SoHo and the industrial buildings of Portland’s Pearl District.

A quick blurb on each:

“SoHo is known for its artsy crowd, with painters, sculptors, artists (and now celebrities) of every kind living in lofts with square footages and ceiling heights unimaginable to most New Yorkers. Without these lofts, however, New York’s creative reputation would not be what it is, as these artists would have otherwise been quickly priced out of the city. What allowed so many NYC artists to thrive in these lofts for decades without being displaced by New York’s real estate frenzy? Legislation commonly known as the Loft Law is a primary answer.” - SoHo Broadway Initiative

“Primed by industry, the [Pearl] district developed into the Northwest Industrial Triangle, made up of rail and warehouses. Half a century later, the industrial backdrop gave way to art and creativity. Artists turned warehouses into studios, galleries, and businesses supporting the creative culture, and in 1986, 13th Avenue from Davis to Johnson Street officially received a historic designation from the city.” - Pearl District Portfolio

Once artists get a neighborhood established, it becomes the next big thing, and developers swoop in to buy up the properties. Artists are often encouraged to remain in these areas by developers who need to retain the neighborhood’s character to attract buyers and lessees. However, over time, artists tend to be casualties of economic prosperity. Artists and arts organizations may be given limited-time subsidies to remain as the neighborhood gains recognition and property values rise. But they are eventually replaced by luxury retail and chain stores. The Pearl District historic designation did not cover the rights or needs of living artists. NYC’s Loft Law did not protect against rising rents and escalating property values. It “protected and legitimized loft living” in the 1980s and 1990s, but few artists remain in the area in 2024. Artists don’t live in $20 million dollar lofts. Private equity guys live in $20 million dollar lofts.

Asheville’s River Arts District

Asheville’s River Arts District was in the middle of a similar transition when Helene hit. A brief and incomplete history:

Artists began moving to the riverside in 1985, at the first glimmers of Asheville’s downtown revitalization. Helaine Greene and her sister, Trudy Gould, bought Riverview Station in the 1980s; it’s now home to 60+ artists’ studios. Pattiy Tornio founded Curve Studios in 1989; by 2021, the building was allegedly worth around $2 million, but she was vowing to stay put.

In 1994, The Odyssey Center (now known as The Odyssey Center for Ceramic Arts) hosted the first “Studio Stroll,” which is now a massively popular tourist attraction. Artists began to assemble, and the neighborhood began to take shape. Marty and Eileen Black bought The Cotton Mill Studios Mill for their own practice in 2003, then opened it up to other artists, and the current owners bought the building for $1.95 million in 2017.

In 2005, the city officially named a mile-long section along the French Broad riverfront “The River Artists District.” No one seems to remember when John Payne opened Wedge Studios, which houses 30 artists’ studios. It feels like it’s been there since the dawn of time, but Wedge Brewing debuted in 2008.

Collector Hedy Fischer and artist Randy Shull bought the Pink Dog Creative building on Depot Street in 2010; like Torno, they have plowed resources into Asheville artists as the neighborhood changed with dizzying speed. The River Arts District Business Association (“RADBA”) was created in 2011, and River Arts District Artists, Inc. (“RADA”), a nonprofit member organization of independent artists, was formed in 2013.

However, the RAD is also a city-designated hotel zone, and many have long been eager to see the area converted to a tourist destination with the draw of Asheville’s immensely popular downtown. When I moved to Asheville in 2015, the local art scene was abuzz with questions about the fate of the Phil Mechanic building, considered a bellwether for the RAD’s future. It was sold to Georgia-based Hatteras Sky, which built a boutique hotel next door.

Private development continued to bloom. Construction began on The Wyre, a 245-unit living, commercial, and retail complex in 2022. (It’s still unfinished.) In the same year, the city approved another 263-unit megalith. Both agreed to provide around 5% of units at 80% area of median income for a minimum of 10 years (or 20 years, depending on who you ask and what stage of the project we’re discussing), but these units are not reserved for artists. Plus, Asheville doesn’t have a strong history of extending such incentives.

According to Asheville Watchdog’s 2024 investigative report of county tax records, studio locations in the RAD showed assessed increases of 30 to 50 percent from 2017 to 2021.3 It’s hard to hold against that kind of tide. Even dedicated arts supporter Fischer feels the pressures of time and change: “A lot of us that own buildings down there are well into our retirement ages…We’re all sort of aging out…I think that’s something that’s going to cause change in the district.”4

Artists Moving On

Predictably, this progression was unsustainable for members of the creative community, just as it was for artists in SoHo and the Pearl District. Hundreds of artists still work in the RAD, but others have moved to the “Little River District” on Mulvaney Street or smaller towns such as Marshall, NC.

Mulvaney Street and Marshall were smashed by Helene.

Note the location of the Antique Tobacco Barn, a massive antiques mall with 75 vendors. Here’s what the ATB looks like now:

Marshall High Studios, a breathtakingly romantic island-high-school-turned-studio-space that housed 30 creative practices, is destroyed.

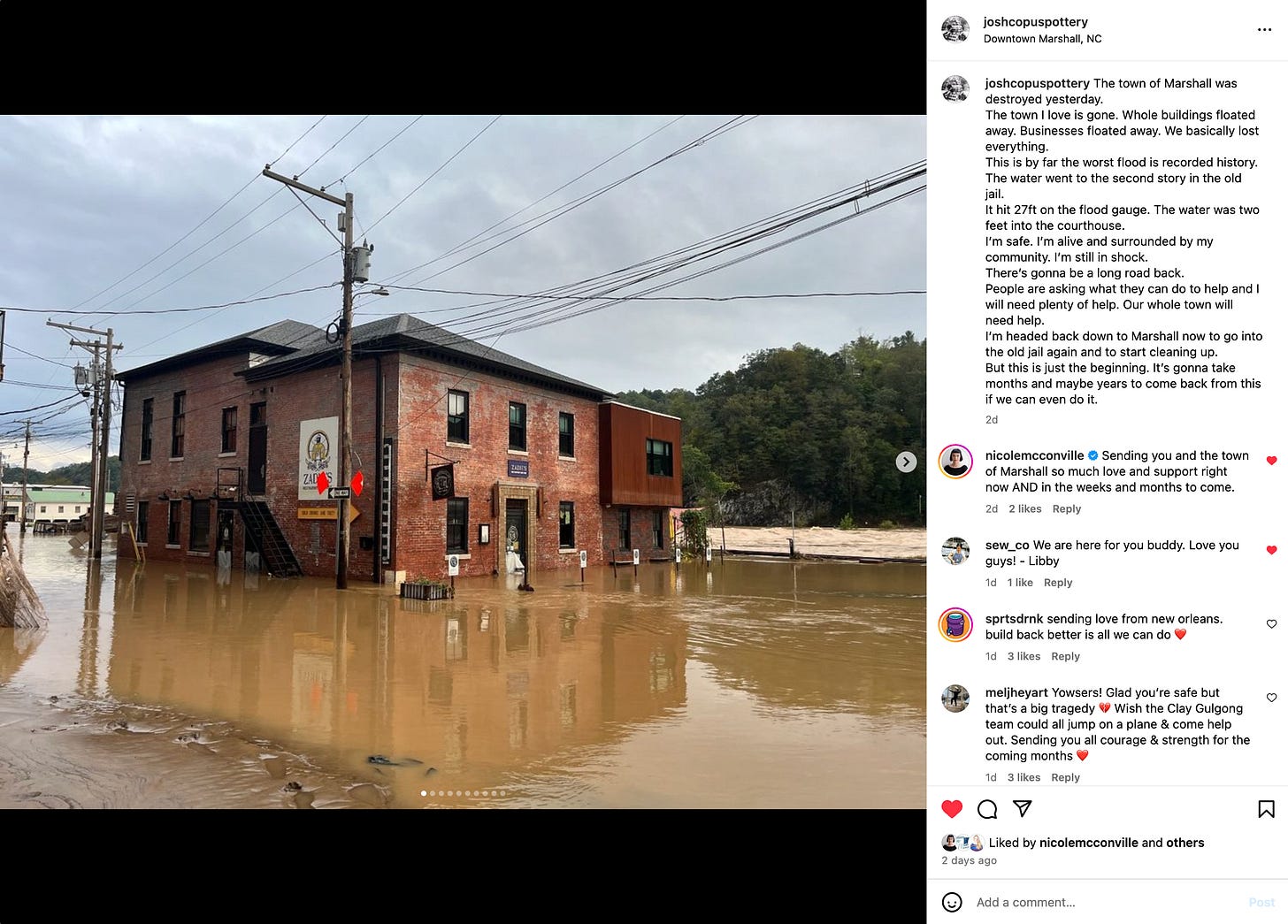

Artist Josh Copus’ Instagram is full of heartbreaking images from Marshall. I’m glued to his feed because I still haven’t heard from our Marshall clients and friends.

When Disaster Strikes

Artists are particularly vulnerable members of any urban population because they 1) seek low-cost studios and housing in former industrial zones, 2) experience dramatic cost escalation when developers “discover” these transformed areas, and 3) are eventually forced to give up their studios and housing because of price increases and city policies that favor development. Plus, 4) artists’ assets tend to be heavy, unique, and challenging to move.

If disaster strikes when conditions 1), 2), and 4) exist simultaneously (artists pooled in an area, prices rising rapidly, lots of objects on site), then artists find themselves in an extremely precarious position. Artists clustered in the RAD were already stretched financially because of development and have now lost the assets (finished artworks, raw materials, and equipment) they need to survive.

While I was writing this essay, an artist who works in the Cotton Mill Studios called. She told me the air reeks of gas due to all the leaks and that people are being told to avoid the bridges because they may collapse imminently. She told me looters are expected by sundown. She’s deciding whether or not to risk her personal safety to rescue her artwork, tools, equipment, furniture, and personal effects.

Artists in the River Arts District, Asheville, Marshall, Mars Hill, Black Mountain, and other mountain enclaves are exceptionally vulnerable right now. They need humanitarian aid in the form of direct help, federal help, and nonprofit assistance. However, they also need some strategic help to preserve the artistic culture of Western NC. There is no guarantee that the state, city of Asheville, local towns, or private interests will restore these creative enclaves. If a climate disaster strikes when artists are pooled in any area where property development contributes to rapid price increases, they find themselves in an extremely precarious position.

Up Next…

Next Tuesday (10/8), I’ll be back with a second installment explaining the history and meaning of “cultural heritage,” a term that originated in the 19th century and was codified after World War II by nonprofit organizations and political groups—most notably, UNESCO. If this is your PhD dissertation, please get in touch at hello[at]implementlegal.com. I’d love to talk.

More on The Climate Haven Myth

Supplemental reading for you:

The New Republic, Climate Change Does Not Care About Your Borders

ABC News, Asheville tragedy shows there are no climate change safe havens

The Daily Beast, Hurricane Helene Turns City Touted as ‘Climate Haven’ Into ‘Apocalyptic’ Disaster Zone

The Guardian, ‘Nowhere is safe’: shattered Asheville shows stunning reach of climate crisis

Fast Company, Asheville has been called a ‘climate haven.’ There’s no such thing

How to Help:

Help the artists of Western North Carolina with one or more of these next steps:

💰 Donate, donate, donate. My family is sending blood and money via the Red Cross. Blue Ridge Public Radio has the most reliable list of organizations. Pick your favorite and give what you can.

📸 Engage with me on Instagram. I’m going to feature one Western North Carolina artist each day and let you know how to help them directly via Venmo, Paypal, a preferred nonprofit, or a purchase. Government and 501(C)(3) aid isn’t there yet.

⚖️ Volunteer. My firm is offering emergency pro bono services to affected artists, and we’re focusing our efforts on the River Arts District. Lawyers, property appraisers, paralegals, conservationists, archivists, and art historians who want to help can reach out to me at hello[at]implementlegal.com.

The Rolling Stone article is paywalled, but is quoted by WUNC. Let’s use the source you can access, right? Tom Fiedler/AVL Watchdog, “Come Hell Or High Water, Asheville Is Climate ‘Winner’,” WUNC, March 17, 2021.

I truly don’t fault Mosaic or any other realty group. After all, a Mosaic realtor sold my house in 2021. We lost count of the offers. Buyers stalked me. Demand was INSANE.

John Reinan, “Development in River Arts District fuels concerns about its future,” Asheville Watchdog, March 13, 2024.

Reinan, again. You should read the whole thing. Asheville Watchdog is fabulous.

Thank you for writing this! I recently came across a photo book about the Loft Law and its few remaining beneficiaries but I had not thought about that, until now, as just one example of this phenomenon you describe about artists and where they live and work. Thank you for connecting the dots for me!

Thank you for this!